By C.M. Schmidlkofer

The opportunity for commissioned work arises at least once in a professional craft artist’s career. As in all business ventures, what you know can make the difference between success and failure.

The opportunity for commissioned work arises at least once in a professional craft artist’s career. As in all business ventures, what you know can make the difference between success and failure.

Commissioned work could be a piece of jewelry custom designed for an individual, a sculptural installation for a corporate office or a stained glass window for a public building. If done successfully, commissioned work can catapult a craft artist’s career to another level both artistically and financially.

Alan Bamberger, a San Francisco-based art consultant, said that with a little planning, patience and the right attitude, commissions can be an enjoyable venture. He suggests that the concept of commissions is vastly different than making and selling art on a retail or wholesale basis. Commissions require diligent communication with the client, be it an individual or a public or corporate entity.

That means you must be committed to carrying out what the client wants by working to their specifications rather than your own. “If you’re not comfortable with that, you should probably not do commissions,” he comments. He also advises art lovers seeking commissioned work to choose one artist to work with. This is good advice for artists as well. “Choose one person who is the decision maker, not the husband and others, when it comes to private commissions,” he maintains.

Another tip of advice: before beginning, collect a deposit based on a percentage of the total cost. The overall cost should include the cost of any necessary prototypes, he explains. A written contract spelling out the terms is another good practice for both the consumer and the artist.

Peter and Marilu Patterson of Illinois learned the basics of commissioned work by trial and error. Their advice reflects that of Bamberger’s when it comes to taking on a commission. Peter sells his contemporary blown glass at retail and wholesale shows and teaches the art of glassblowing to an ever-growing number of students.

Peter and Marilu Patterson of Illinois learned the basics of commissioned work by trial and error. Their advice reflects that of Bamberger’s when it comes to taking on a commission. Peter sells his contemporary blown glass at retail and wholesale shows and teaches the art of glassblowing to an ever-growing number of students.

He enjoys the artistic challenges commissions provide—challenges that he may not ordinarily experience in his day-to-day work. During his 30 years in the business, he’s taken on commissions for one-of-a-kind designs to mass producing items for individuals and businesses.

Most of his business comes from the art shows he attends. After seeing his work, people will approach him for a commission. Because commissions are only about 5 to 10 percent of his business, he can afford to be picky about taking them. “I only take the things that interest me,” he maintains. “If it’s something I haven’t done before, I am getting paid for learning.”

Customer satisfaction is of primary importance to Peter and he’s not opposed to working on a project until the client is happy. He remembers a commission where he made a large glass bowl based on a design the client suggested, “I ended up making three of them before he liked one.” For Peter, the effort was not a loss, as he sold the two additional bowls to other buyers at full retail price.

Luck was with him again when he agreed to make lampshades for a lighting company and hadn’t calculated the cost to drill holes in the glass shades. When he realized his mistake, he worked out an arrangement with the clients to do their own drilling while he received the agreed-upon payment.

Marilu wasn’t so fortunate with her first contract oversight. Her client demanded she fulfill the order despite an unforeseen price increase in the platinum used to create his one-of-a-kind ring; she was forced to accept a financial loss. “I learned my lesson that I can’t go back on my word after giving an estimate.”

Marilu wasn’t so fortunate with her first contract oversight. Her client demanded she fulfill the order despite an unforeseen price increase in the platinum used to create his one-of-a-kind ring; she was forced to accept a financial loss. “I learned my lesson that I can’t go back on my word after giving an estimate.”

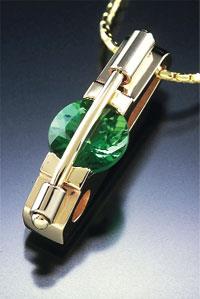

She has been creating contemporary jewelry for more than 20 years, with commissions comprising about 20 percent of her overall sales. About 5 percent of that involves people bringing in stones for her to use in one-of-a-kind jewelry items. Her clients are typically females between 30 and 50 years of age who are buying for themselves. “Sometimes I like commissions because I don’t have the cost of inventory. The hardest thing is getting people to trust you that it will come out the way they want.”

Before contracting with a client, Marilu agrees to provide a sketch and a wax prototype to give them an idea of what the finished project may look like. The client pays for the cost of the prototype if they decide not to pursue the commission. If they choose to go forward, the contract includes up to three prototypes, painted to look as much like the finished project as possible.

Individual consignments are only one type of commission. For those who create larger works, corporate, museum and government commissions are ideal options for self-promotion and income.

Many states have taxpayer-supported programs to promote art in the state. These programs designate a percentage of an estimated renovation or building project to be spent on commissioning and installing artwork. If a state has this type of program, information and applications can be found on its website.

There may be a selection committee that publicizes a call to artists to apply for a particular project. Irene Finck, coordinator of Ohio’s Percent for Art Program, says the selection committee is relying heavily on the program’s online registry as a time-saving device. The registry is open to artists not only for large, sculptural works, but for craft artists as well, and is not limited to the state of Ohio. Registering can open up other sources of commissions as exhibition planners and curators seeking artists are referred to the registry.

There may be a selection committee that publicizes a call to artists to apply for a particular project. Irene Finck, coordinator of Ohio’s Percent for Art Program, says the selection committee is relying heavily on the program’s online registry as a time-saving device. The registry is open to artists not only for large, sculptural works, but for craft artists as well, and is not limited to the state of Ohio. Registering can open up other sources of commissions as exhibition planners and curators seeking artists are referred to the registry.

Finck adds that since the creation of the program in 1990, the average acquisition has been for large sculptural items for state projects, including new building projects and renovated or rehabilitated building projects.

Museums are another source that may publicize a call for artists for a particular program. In 1972, the Smithsonian American Art Museum held a national design competition for the entrance gates of its Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. Jeweler Albert Paley won with his decorative metalwork doors, “Portal Gates.”

Laura Baptiste, Smithsonian American Art Museum spokesperson, says the commission was the first and only one for the gallery, though the gates are considered part of the museum’s overall art collection. “This commission is widely recognized as a turning point in Paley’s career in that it led to more commissions and world renown for his monumental architectural ironwork and sculpture,” Baptiste adds.

Some artists seek out commissions, while others let the work come to them. Either way, commissions are a great way to increase income and expand an artist’s creative talents.TCR

Work by Marilu Patterson, (847) 537-5688.