The verdant hills and dark hollows that surround potter Keith Lahti’s home in the rugged Appalachian Mountains of central West Virginia belong to one of the oldest mountain ranges on Earth. Exposed rock formations found along riverbanks and cliffs offer a timeline in geology and natural history reaching back to the earliest days of mankind and millions of years beyond.

The verdant hills and dark hollows that surround potter Keith Lahti’s home in the rugged Appalachian Mountains of central West Virginia belong to one of the oldest mountain ranges on Earth. Exposed rock formations found along riverbanks and cliffs offer a timeline in geology and natural history reaching back to the earliest days of mankind and millions of years beyond.

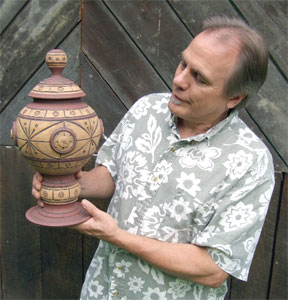

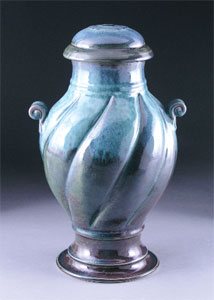

After working with clay for over 35 years in the shadows of this awe-inspiring environment, it’s little wonder that Lahti’s creations are so thoroughly infused with a sense and spirit of the past, even as he embraces a growing new niche market for memorial urns that has arisen in the 21st century.

Lahti has only focused on making memorial urns for about the past five years, yet they already account for roughly one-third of his overall business. And Lahti says that number is growing steadily as word gets out about his ever-changing series of unique urns.

From his workshop in rural Chloe, W.Va., Lahti already had some 30 years under his belt as a full-time potter when inspiration—one part creative and one part monetary, he maintains—led him to try making memorials.

“I’ve always been fascinated by what people call ‘sacred vessels,’” he notes. “And the other thing that led me was the economic possibilities.” As a member of the so-called “baby boomer” generation, Lahti realized there was an untapped market for unique and custom memorials that this new generation would want as it aged.

“I’ve always been fascinated by what people call ‘sacred vessels,’” he notes. “And the other thing that led me was the economic possibilities.” As a member of the so-called “baby boomer” generation, Lahti realized there was an untapped market for unique and custom memorials that this new generation would want as it aged.

Inspired by ancient traditions and cultures from around the globe, Lahti’s work draws from sources as diverse as traditional African objects, ancient Chinese dynasties and American Indian art. Despite the diversity of these influences, a common denominator in his memorial urns is that they tend to provide a “sense of ancient mystery and ritual,” according to Lahti.

Besides this growing business in handmade memorials, Lahti continues to make functional and nonfunctional pottery. Considering how thoroughly he has immersed himself in a career in clay, it might seem a bit surprising to find that as an art student and aspiring artist in college, he really had no interest in pottery.

Once an artist, always an artist

Born and raised near Detroit, Mich., Lahti always knew he wanted to be an artist. “When I was asked in kindergarten what I wanted to be when I grew up, I drew a picture of an artist living in the mountains in a log cabin,” he notes. Little did he know at the time how closely his career would follow that path.

As an art major at Albion College in Albion, Mich., Lahti focused on printmaking. He took his first pottery class late in his academic career, but only because it was a required course. Much to his surprise, he says, “I thought, ‘Wow, I really like this.’” Unfortunately for his newfound love of clay, Lahti only had time for two pottery classes before he graduated.

As an art major at Albion College in Albion, Mich., Lahti focused on printmaking. He took his first pottery class late in his academic career, but only because it was a required course. Much to his surprise, he says, “I thought, ‘Wow, I really like this.’” Unfortunately for his newfound love of clay, Lahti only had time for two pottery classes before he graduated.

Undeterred by his lack of formal training, he decided to make a living as a potter in the early 1970s. “I learned mostly from a lot of trial and error…a lot [more] of error,” he shares. He recalls that one of the low points of what he sarcastically terms his “auspicious beginning” included taking a load of creations that he considered rejects to the local dump, only to find on his next visit that the workers had retrieved his pieces from the landfill and were selling them for ten cents each.

Building a career in clay

Fortunately, things improved from there. Lahti took courses and workshops, and experimented endlessly with clay. He also fulfilled his kindergarten aspirations when he fell in love with the natural beauty of West Virginia and bought property with an old cabin in the mountains. He built a studio there and started to earn a decent living as a potter.

Over the years, Lahti steadily built his business at a comfortable pace. Working with earthenware and stoneware, he has purposely maintained a one-man studio, with just a bit of part-time help. Nowadays, his non-memorial work is featured in a handful of galleries and on one online craft site. He is also a featured artist in the acclaimed Tamarack craft center in Beckley, W.Va., which serves as a showcase for many West Virginia artists. Despite his rural location, Lahti maintains he also does a fair amount of business from walk-in traffic at his studio.

Marketing memorials

Of course, memorial urns are in many ways an entirely different kind of product than functional pottery, and Lahti recognized early on the need to market the urns on their own. He has a website, handmadecremationurns.com, that is devoted exclusively to his memorials.

Of course, memorial urns are in many ways an entirely different kind of product than functional pottery, and Lahti recognized early on the need to market the urns on their own. He has a website, handmadecremationurns.com, that is devoted exclusively to his memorials.

When he started creating his memorial urns, Lahti carefully considered what would be appropriate ways to market this work. “To reach a wider audience, I think the website is appropriate,” he concludes.

About half of his memorial urn sales now come from his website, and about half come from people who have seen or heard about an urn Lahti made for someone else.

He also tries to maintain an inventory of a couple dozen urns already made and available at all times for customers who need one immediately. For those who can wait, he is able to customize urns to meet special design requests.

The personal connection

Lahti knows he must remain even more responsive to the needs of customers buying his memorial urns than to buyers of his other pottery. “The urn becomes a sacred object,” he believes.

Despite the sadness that accompanies the death of loved ones, Lahti finds at times his memorials can help ease the sense of loss in some small way by being part of an important ceremony for survivors. He finds the process uplifting, and never morbid. “To me, it’s part of human life,” he emphasizes. “It’s part of the ritual of human life.”

Keeping busy

Keeping busy

Outside his studio, Lahti finds inspiration and relaxation enjoying the 80 acres of property he owns. He gardens extensively, and also finds time to play guitar as half of a blues-and-folk-rock-tinged duo named Holy Cow. And Lahti serves as vice chair of the Tamarack Foundation, a nonprofit group that works to support programs for West Virginia artists.

He maintains a comfortable level of pottery work, balancing the growing demand for his memorial urns with his other clay work. Coupled with his non-clay hobbies, Lahti’s work keeps him busy. But you’ll hear no complaints from this one-time, would-be printmaker who fell him in love with clay and never turned back. HB

Mike Ricci is the former art director of The Crafts Report, and is currently a freelance writer and designer. You can reach him at mricci7165@comcast.net.