By Daniel Grant

There are many questions that fine artists have at the outset of their careers: Where can I show and sell my work? How do I find prospective buyers? Do I need a dealer? A question that probably doesn’t not arise is, how do I make the whole process more opaque?

Perhaps, the answer is by transforming artworks into “digital assets” and making the purchase or rental of them using cryptocurrency — at least, that is what the New York City-based DADA (dada.nyc/home) aims to do.

Making money off collaborative art conversations

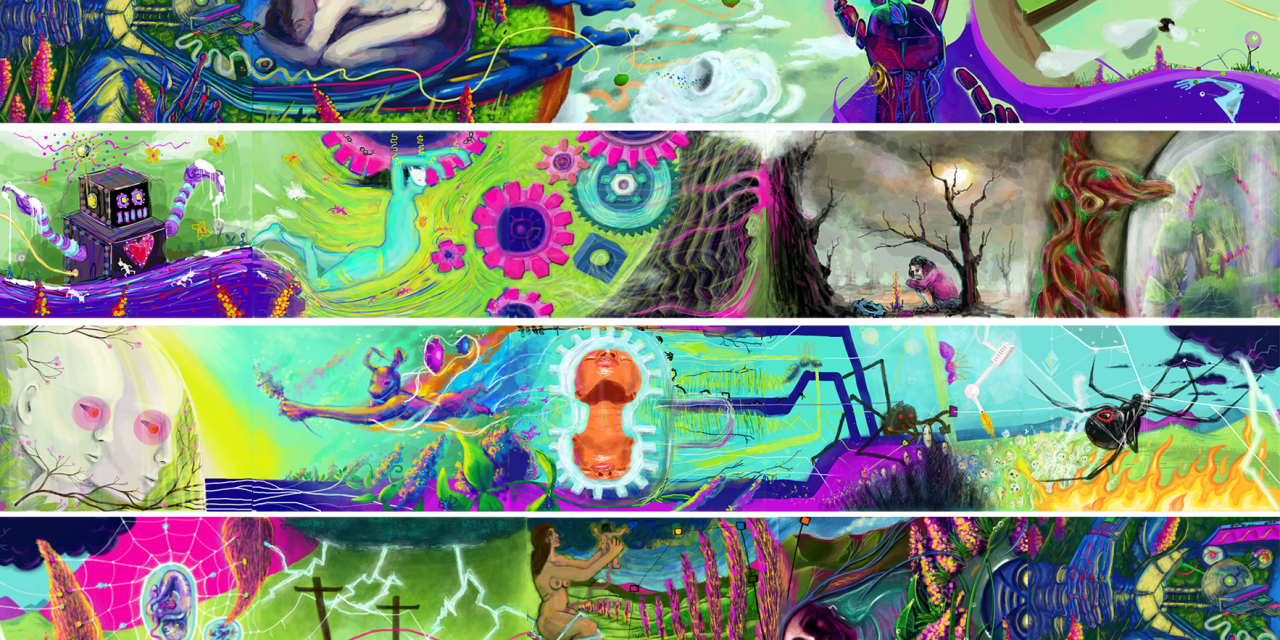

According to DADA’s founder and chief executive officer Beatriz Helena Ramos, the company was started in 2014 with the idea of “creating a platform for people to have conversations using visual images.” Artists go onto the web site, draw something exclusively using DADA’s own online art tools, and it is hoped and expected that artists elsewhere would reply with other images that play off the first artists’ drawings. “It’s a way of doing collaborative art,” she said, “a social way of making art.” So far, the site contains over 100,000 drawings or, as Ramos describes them, “the largest collection of provably rare digital artworks in the world, ready to be traded as non-fungible tokens.”

Last year, DADA began selling images from its Creeps & Weirdos collection — dada.nyc/artgallery — as a proof of concept. During that period, 700 images were sold for 15 ETH — using the cryptocurrency Ethereum, an alternative to bitcoin— which is exchangeable for $1,300 or so. The January launch expanded the roll-out to all of the growing supply of images, and “people are able to license any of our drawings — using smart contracts — and they are able to buy drawings for popular visual conversations.”

Whether or not artists will make money through DADA is anyone’s guess. Artists do not “put a price on their work, market, sell or negotiate at all,” Ramos said, as prices are determined “by the community” of DADA members, and “each collector decides the value the art has for them.” Initial prices so far have proven to be quite low, and the best prospect for income is if images are resold or relicensed repeatedly and at ever-higher amounts.

Returns on the investment

Those “smart contracts,” embedded code in the images that track primary and secondary market sales, as well as rental arrangements, represent the new technology that turns a shareware platform into a potential money-making business venture. To date, a small group of investors – including Ramos, an illustrator, and Yehudit Mam, a creative director and writer, as well as several companies in the tech field – have invested $800,000 in DADA, the bulk of which has gone to a team of designers and web developers. However, she noted that DADA has attracted several investors, including ConcenSys (consensys.net) a company specializing in “decentralized technology,” such as Ethereum, and DADA is now valued at $10 million.

Not only does this start-up see its way to profitability, so too should starting-out artists, she claimed. When an artist’s drawing — “we call it a conversation, not a drawing, because the art is the collaboration,” Ramos said — is sold or licensed for use on products — such as t-shirts or album covers — or in advertising, the artist who did the original image receives 70 percent of the proceeds, while the remaining 30 percent is divided among the entire DADA community, which currently consists of 160,000 registered users — mostly artists, consumers and people Ramos calls “appreciators.” A portion of that originating artist’s cut is shared by the other artists who contributed to the “conversation.” The artist and entire DADA community get paid again if a buyer of an image resells it at a profit, with 60 percent of the profit going to the seller, 20 percent to the artist and remaining 20 percent to the community.

Stifling art

Artists set their own prices, but the only artwork they may sell on DADA is what they produced on the web site. They may not upload works that they created in their own studios, which Ramos called “personal art,” to be sold on DADA. For that reason, the platform is more likely to appeal to younger, less experienced artists than to those whose artwork exists as actual physical objects and that may have their own collectors.

In the current art gallery system, she said, “a small percentage of artists gets all the money and everyone else gets nothing. Ninety-nine percent of all art students quit the field of art right after graduation.” DADA’s share-the-wealth ethos would enable artists to get “a basic income and make a living.”