By Stephanie Finnegan

Frequently a person will say, “Let my work speak for itself.” The artist doesn’t want to clutter a spectator’s takeaway with an imposed philosophy or a forced conclusion. When Bruno Walpoth utters those words, he means this declaration both modestly and meaningfully.

A man of few words—but those that he shares are choice—Walpoth is like the Spencer Tracy of the sculpting world. Just like that legendary American actor who downplayed his greatness by reducing his craft to “know your lines, come to work on time, and don’t bump into the furniture,” Walpoth treats his achievements as if they are just part of his daily routine. His job is that of a wood craftsman—a sculptor who creates with that most natural and organic of elements. He makes lifelike figures. What’s the big deal?

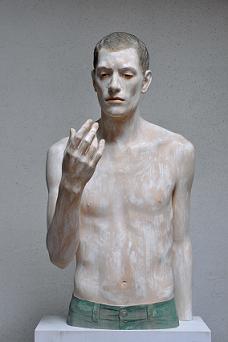

Well, according to esteemed art historian Lisa Trockner, “The life-size young women and men that have been extracted appear motionless. It appears as if in the very moment of being brought to life by the hand of the artist, their movements again have become paralyzed. Their haggard bodies stand there with frozen gestures and facial expressions; their arms stretched out either before them or sideways, but only rarely bent or intertwined. In their decidedly tense poses, Bruno Walpoth’s full-figure sculptures, along with his torso-less and legless busts, appear introverted, static, and unaffected by their surroundings. Sometimes their gaze is averted and other times it is straight ahead and directed toward the viewer. Their eyes do not wander in search of contact. They are not trying to catch the eye, rather—as is consistent with their pose—they are fixed in concentration and directed inwardly. The pupils are dull and the lids sometimes even closed; their gaze in any case remains tangible. They generate presence in space.”

Born in 1959 and raised in Italy, Walpoth comes from a family of artists. His grandfather and uncle were both sculptors, and wood was the medium he grew up with. A virtuoso with lime wood, nut wood, birch, and walnut, among other preferred source material, Walpoth utilizes a chisel and file to free his creations from their original shapeless confines.

Under his coaxing, men and women emerge from these blocks of wood. They seem to have been roused from slumber and are just now gaining their bearings. The Walpoth creations are meditative and introspective—having been dreamed up by a visionary artist, they are possibly caught up in the last stages of a dream themselves. Unlike a subject who is smiling broadly for a photographer or preening for a portraitist, these characters are stripped of artifice and pretensions. They seem so real because they are so vulnerable and honestly off guard.

“When I make my sculptures, I am not telling any stories,” he stresses. “I am just trying to capture the moment. That moment—in which the model has vanished in his own thoughts and acts ‘absent’—is what interests me the most. It is this moment I am trying to implement. The melancholic mood comes from being alone. Maybe it’s a longing for something, which I carry in me.”

The muses for his sculptures are grounded in reality. They represent friends and family—his three sons have consented to serve as models from time to time—as well as people he has seen and was touched by on the street. Viewing everything with the eyes of an artist, a passing glance from a passer-by can trigger a need to capture that expression. The biography of the person who has impressed him does not matter. He is not looking to write a narrative or proselytize a theme—“I don’t want to communicate any message and certainly not to convey a lesson. It comes to me solely and exclusively as a state to hold a moment of human existence.”

Since his works are lifelike in size and in proportion, their “physical aesthetics” say much about their connection to being human. But beyond their actual dimensions, Walpoth points to the sculptures’ expressions: “When standing in front of the work, one should have the impression that the characters have a soul. I would like to achieve that.”

There is no doubt that he has accomplished that goal.

“Each new figure is a challenge, an attempt by the artist to breathe a living soul into carved wood,” says art critic Trockner. “The true-to-life form of the body is the means to an end—the conveyor of the psyche. The viewer has turned inside out while imagining the mental state of the figure. Walpoth’s figures are not a revival of lost ideals, but rather through the presence of the public, they are repositories. They reflect the viewer’s own store of impressions.”

The response to his sculptures has been universal, and C.A.M. Gallery, located in Istanbul, Turkey, has become a major proponent and exhibitor of his work. “The gallery owners, Sevil Binat and Levend Binat, visited Bruno Walpoth at Ortisei, his hometown. They saw his studio and experienced the way the artist works. The way he shaped wood really affected them. For us, in addition to the details on the wood, we are touched by the way he gives life to his sculptures. Their expressions make them alive and form a bond with the viewer,” Melek Gencer, associate director of C.A.M. Gallery, relates.

“As an established contemporary art gallery in Istanbul, we are very interested in exhibiting sculptures. However, we are aware of the lack of sculpture as the medium in Turkey. In today’s contemporary art market, it is a chance to meet Bruno, who works with wood and forms figural sculptures,” Gencer continues. “We have started showing Bruno Walpoth’s works last year at Contemporary Istanbul Art Fair, 2012. Since then we have received great reactions from our collectors and viewers. It is great to show his work and introduce him to the Turkish market. We hope our partnership lasts; he is a very special artist.”

Alexandra Badke, a representative of Galerie Frank Schlag & Cie, of Essen, Germany, one of the sculptor’s European dealers, points to the critiques of Lisa Trockner to showcase how minimalist yet monumental Walpoth’s work is: “Frequently the wooden figures are naked or only partially clothed, so that the bone structure of the apparently androgynous bodies, which he predominantly favors, is made clearly visible. While the unclothed parts of the figures have been sanded down smoothly and exhibit a skinlike texture, the clothed or hirsute areas are rougher, displaying traces of the chisel or of being painted with pastel-like pigment. The smoothly polished skin shows traces of white paint: permanent ‘whitening’ of the naked areas of the body is achieved through meticulous sanding, working the paint on the surface into the wooden material, thus reinforcing the pure, virtually translucent character of the skin while simultaneously dehumanizing it. The wood’s matter itself becomes transformed—even more so when coated in white—appearing dematerialized. The material itself therefore becomes irrelevant; it is rather the form that is highlighted.”

The form and the anatomy of the sculptures matter to Walpoth, and he acknowledges that “the silent poses of the figures of the Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca still impress me. Among the contemporary artists, I very much admire the works of Antony Gormley, as well as the busts of Katsura Funakoshi. Additionally, the photos of the American photographer Jock Sturges fascinate me. In fact, for a while, I used his images as inspiration for my sculptures.”

When asked if he believes his work is influencing and inspiring others, he is flattered. “I have taught 22 years at a school, so I have been a teacher. I gave up the job five years ago so I could devote myself fully to sculpture. Are other artists learning from my work now? I don’t know! It could be possible.”

His studio filled with still-life creations stand as quiet, serene accomplices for ensuring his legacy.

Bruno Walpoth, walpoth.com; C.A.M. Gallery, www.camgaleri.com; Galerie Frank Schlag & Cie, www.galerie-frank-schlag.de